The American Folklore Legend of Slappy Hooper, Sign Painter

The telling and retelling of 'Slappy Hooper, World’s Biggest, Fastest, and Bestest Sign Painter'.

This month saw the reissue of Aaron Shepard and Tony Goffe's picture book, The Legend of Slappy Hooper. It was first published in 1993, but Slappy Hooper's story goes back to the 1930s, as Shepard details in his author note:

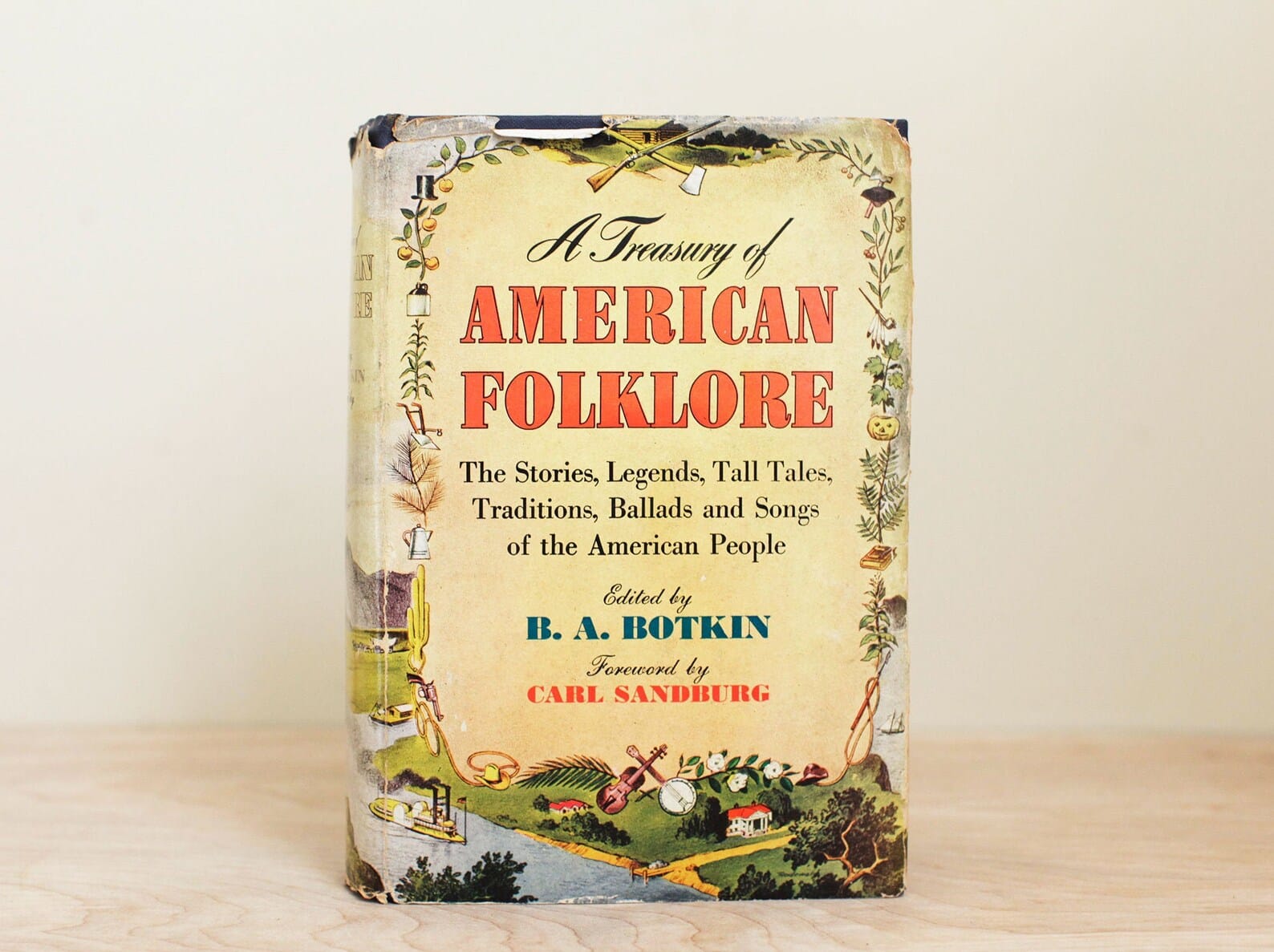

"The legend of 'Slappy Hooper, World’s Biggest, Fastest, and Bestest Sign Painter' was collected in Chicago in 1938 by Jack Conroy for the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration. It was first published in B.A. Botkin’s A Treasury of American Folklore (Crown, New York, 1944)."

Botkin's book runs to nearly 1,000 pages, just four of which contain the original legend. I tracked down a copy, and have transcribed the story at the end of this post for your enjoyment.

Retelling the Legend

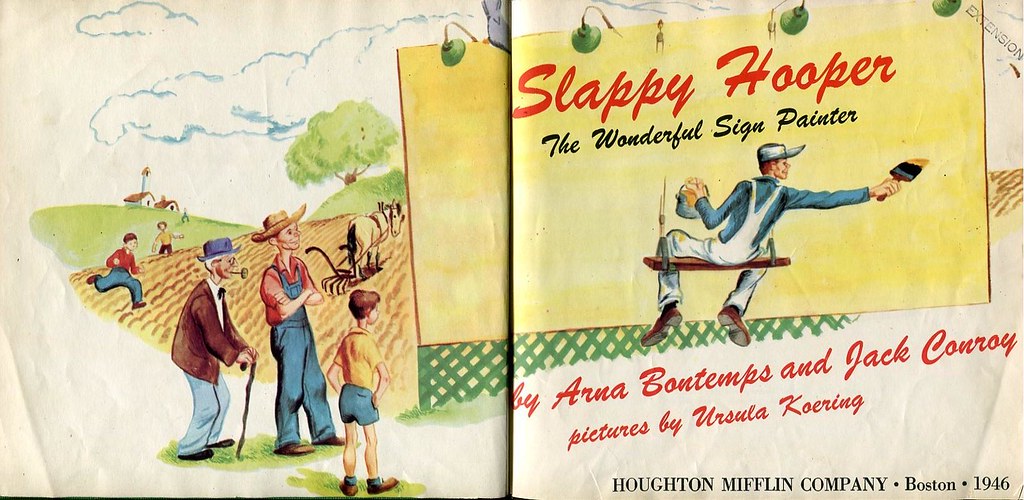

Shepard and Goffe's interpretation is not the only retelling of the Slappy Hooper story. Two years after the Botkin anthology was published, Arna Bontemps worked with Jack Conroy to expand on the legend for a book illustrated by Ursula Koering.

The full book can be browsed here on Flickr and, in an article discussing the collaboration, Ariel S. Winter shares a little of Jack Conroy's background:

"Jack Conroy (1898-1990) was the first worker-writer (a practitioner of socialist realism) in the United States. He grew up in a coal mining camp in Missouri during the early years of unionization, and went to work in the railroad shops nearby at age thirteen. His initial success as a writer came when H.L. Mencken published his work in the American Mercury. Conroy later returned the favor to many young writers as the founder and editor-in-chief of the socialist literary magazine The Anvil where he published Langston Hughes (another chance meeting!), Richard Wright, Nelson Algren, and Erskine Caldwell." — Ariel S. Winter at We Too Were Children, Mr. Barrie

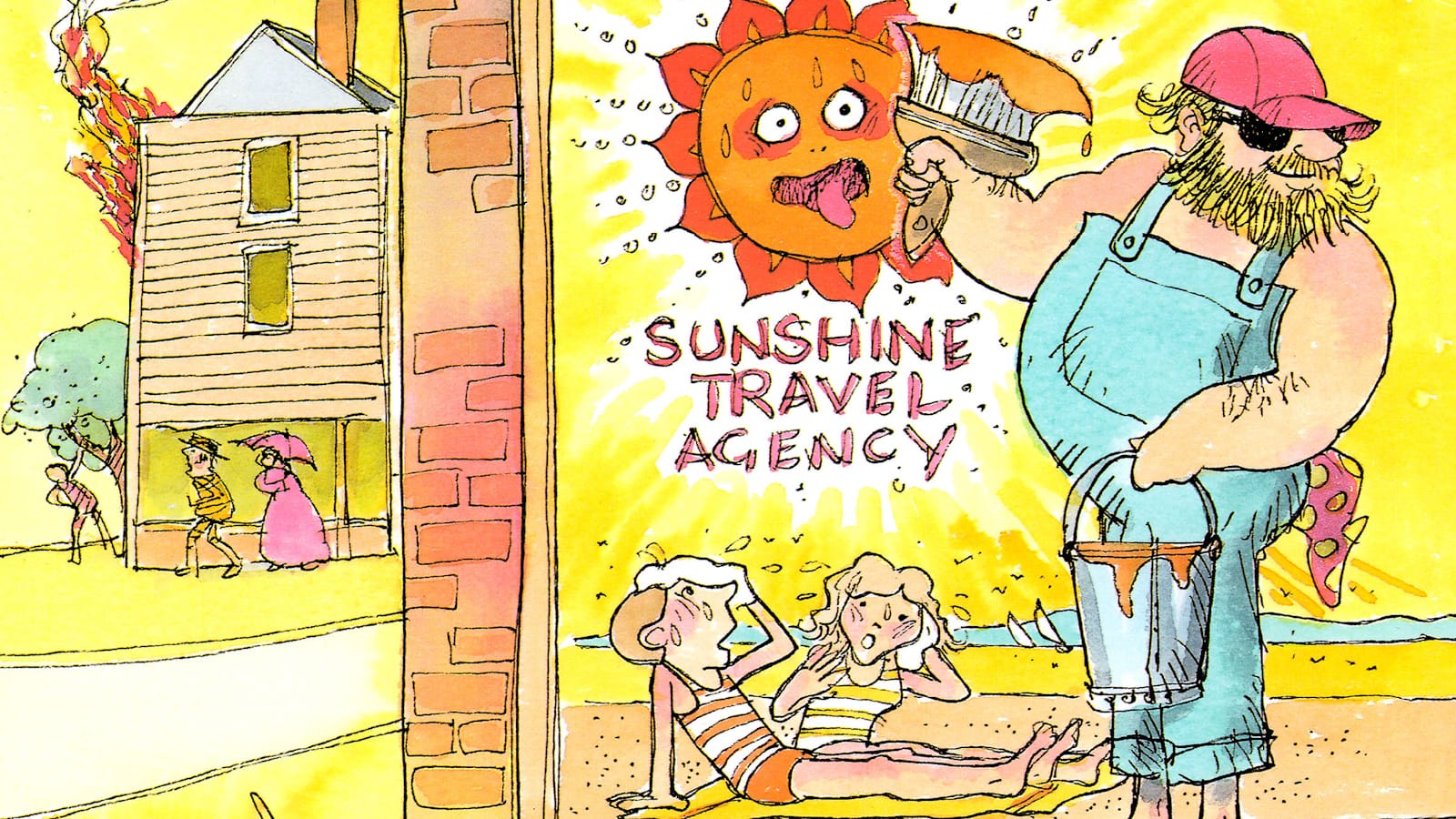

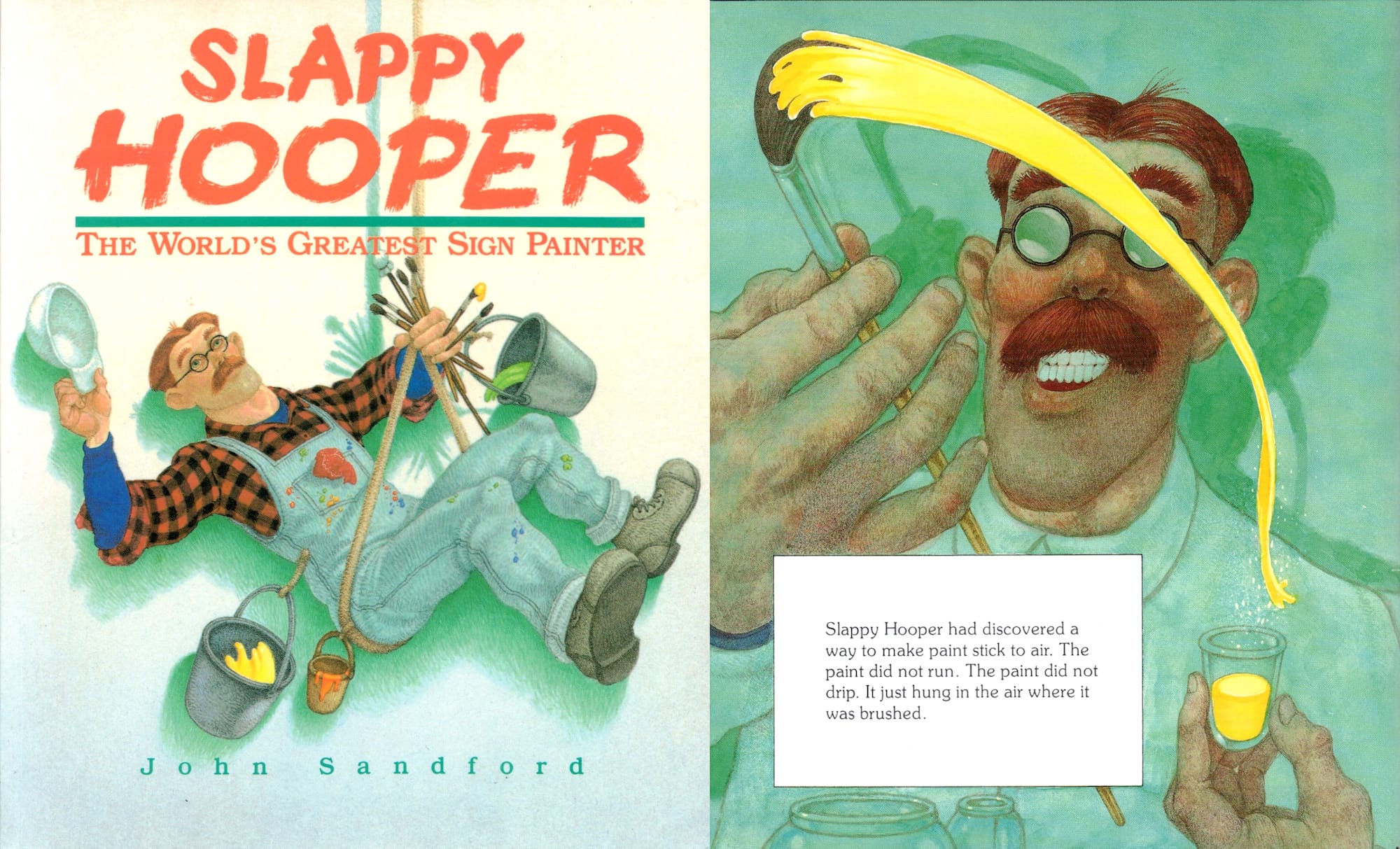

Almost 45 years later, in 1990, John Sandford's Slappy Hooper: The World's Greatest Sign Painter was published by Warner Juvenile Books, a Time Warner Inc. company. Once again, the original legend provided the foundation for Sandford's own storytelling and creativity.

Sandford spent some time working for a Chicago sign shop, which was where he learned of the Slappy Hooper legend. In email correspondence, he wrote:

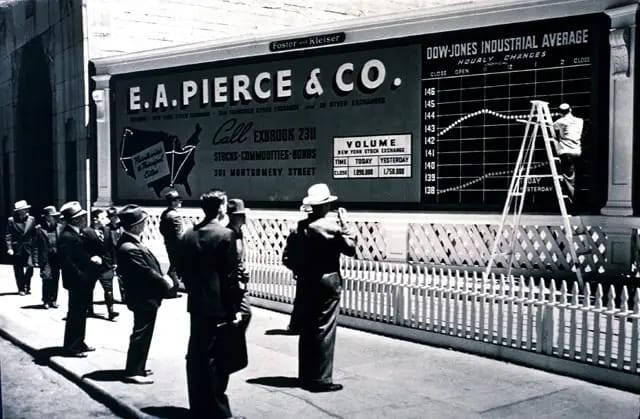

"My knowledge about Slappy came directly from experience working for a sign company in the early 1970s; a union job. When I was in art school, the money dried up, and I had to take a year off to make tuition. I got a job as a pictorial artist at Foster & Kleiser billboards, here on Chicago's south side, in an industrial park built where the old Union Stockyards were once located.

"My coworkers talked about Slappy, and I thought he was real! They tipped their hands when they told about his hanging from the middle of the sign, painting as he swung back and forth—like windshield wipers on a car. I finally realized Slappy was a tall tale. I was a little disappointed, but the stories were endless!

"I put a lot into the book, basing Slappy's look on a couple friends, and the dedication is to my foreman at Foster & Kleiser. It's all loaded with personal references everywhere; I try to do that with my work (children's books).

"The sign painting experience, procedures, working with enamels, oil paint, dryers, extenders, linseed oil, etc, put me years ahead of others when I returned to school. What I believed was a low point in my life, was actually a great blessing—working with long-time professionals was a masterclass, and I wouldn't be me without this." — John Sandford

Sandford wasn't the only one to include personal experience and references in his retelling. Aaron Shepard recalls a key source of inspiration from a family connection:

"The flower and eagle signs in the book were inspired by a sign painter friend of mine and my mother's, a man she used to work for as an office manager, Chuck Ellsworth of Allpoints in Eureka, California. His signs were truly amazing and gave me a great appreciation of the craft."

In the BLAG shop, you can find some copies of The Legend of Slappy Hooper by Aaron Shepard and Toni Goffe. This is the softcover version of their 30th anniversary edition.

Slappy Hooper, World's Biggest, Fastest, and Bestest Sign Painter

And here is Jack Conroy's telling of the original legend, as transcribed from B.A. Botkin's A Treasury of American Folklore.

Slappy Hooper wasn't big because he was six foot nine and wide between the eyes, no more than he weighed three hundred pounds without his cap on or his bucket in one hand and his brush in the other. It was just that there wasn't no job any too big for Slappy, and he never wanted a helper to mess around with.