When ‘Hand-Painted Jamaica’ Met Bug Art Sav

Tracey Thorne profiles Bug Art Sav, a Jamaican sign painter keeping the island’s traditions alive.

When I was pulling together material for Issue 01 of BLAG, I contacted Bug Art Sav in Jamaica to paint the first ever ‘Wise Words’ piece; his ‘Good, Fast, Cheap’ Venn diagram reminds clients that they can have any two of these, but not all three.

I only knew about Bug and his work due to Tracey Thorne’s Hand-Painted Jamaica initiative, which I profiled in 2020 on the former Better Letters blog. Following an exchange with Tracey about the devastating impact of Hurricane Melissa on the island and its sign painters, she shared a profile of Bug that she’d only just published. With her kind permission, I’m delighted to reproduce it here for BLAG readers.

After sharing it last week, lots of BLAG readers donated to Bug’s GoFundMe to help him get his life and business back on the road after the hurricane. Thank you.

If you haven't donated, then the fundraiser remains open and is not far from its ultimate target.

Hand-Painted Jamaica: Bug Art Sav

Words and Photos by Tracey Thorne

In 2018, I began a documentary photography project called Hand-painted Jamaica, an Arts Council England-funded photographic survey of Jamaica’s visual culture, from graffiti and sign painting to street art. It became an ethnographic journey, an attempt to see the island’s visual culture through the eyes of the people who create it. Over months spent in towns and roadside workshops, I met the artists whose work gives Jamaica its colour, rhythm, and identity. One of them was a young painter from Westmoreland, known locally as Bug Art Sav.

Bug’s real name is Rushane Drummond, and his story is rooted in a family lineage of traditional craftsmen. Born and raised near Savanna-la-Mar, he grew up surrounded by Jamaica’s saturated light and visual texture, the typography of hand-painted shopfronts, the murals of dancehall culture, the vernacular poetry of roadside messages. These were his early teachers.

Rushane was, in his own words, “born to be an artist”. Raised in an environment steeped in creativity, surrounded by Jamaica’s natural beauty, pulsating colours, and a long tradition of hand-drawn typography and signage, he developed a style that feels both inherited and entirely his own.

At Frome Technical High School, he majored in visual art but spent most of his free time visiting local sign painters on the streets of Savanna-la-Mar. Under the guidance of professional artists and typographers, Rushane began to blend his influences into a distinctive visual language — bold, witty, and alive with rhythm. In 2009, after passing his CXC in visual arts, he launched his career as an independent artist. Since then, the streets of western Jamaica have borne witness to his bursts of colour, wise and humorous messages, and a typographic style brimming with energy and life.

Since 2019, Bug has harnessed social media and the steady flow of travellers through nearby Negril to expand his reach. His hand-painted signs now travel far beyond Jamaica, carried home by visitors who want a piece of the island’s living visual culture. His commissions range from local shopfronts and bars to collectors and brands who recognise the enduring authenticity of his craft.

In the image below, Bug is seen hand-painting a sign for me to take back to England - Jamaica Jamaica. The letters were carefully pencilled out before he began to paint. Every sign painter’s lettering is unique to their own hand, and after a while you begin to recognise it — a signature hidden in the brushstrokes.

To understand Bug’s work, it helps to see it as part of a much longer story. The history of sign painting stretches back centuries — in Britain, it developed in the eighteenth century alongside urban growth and the Industrial Revolution, when hand-painted signage became a vital form of street communication and advertisement. Jamaica, a British colony from 1655 until independence in 1962, inherited this craft through colonial trade and urban expansion. Yet the island made it its own.

Even earlier, the act of painting on walls — as communication, identity, or ritual — was present in the Caribbean’s pre-Columbian cultures. Over time, these layers of influence fused into something distinctly Jamaican: a visual language that blends colonial lettering traditions with the pulse of Afro-Caribbean creativity.

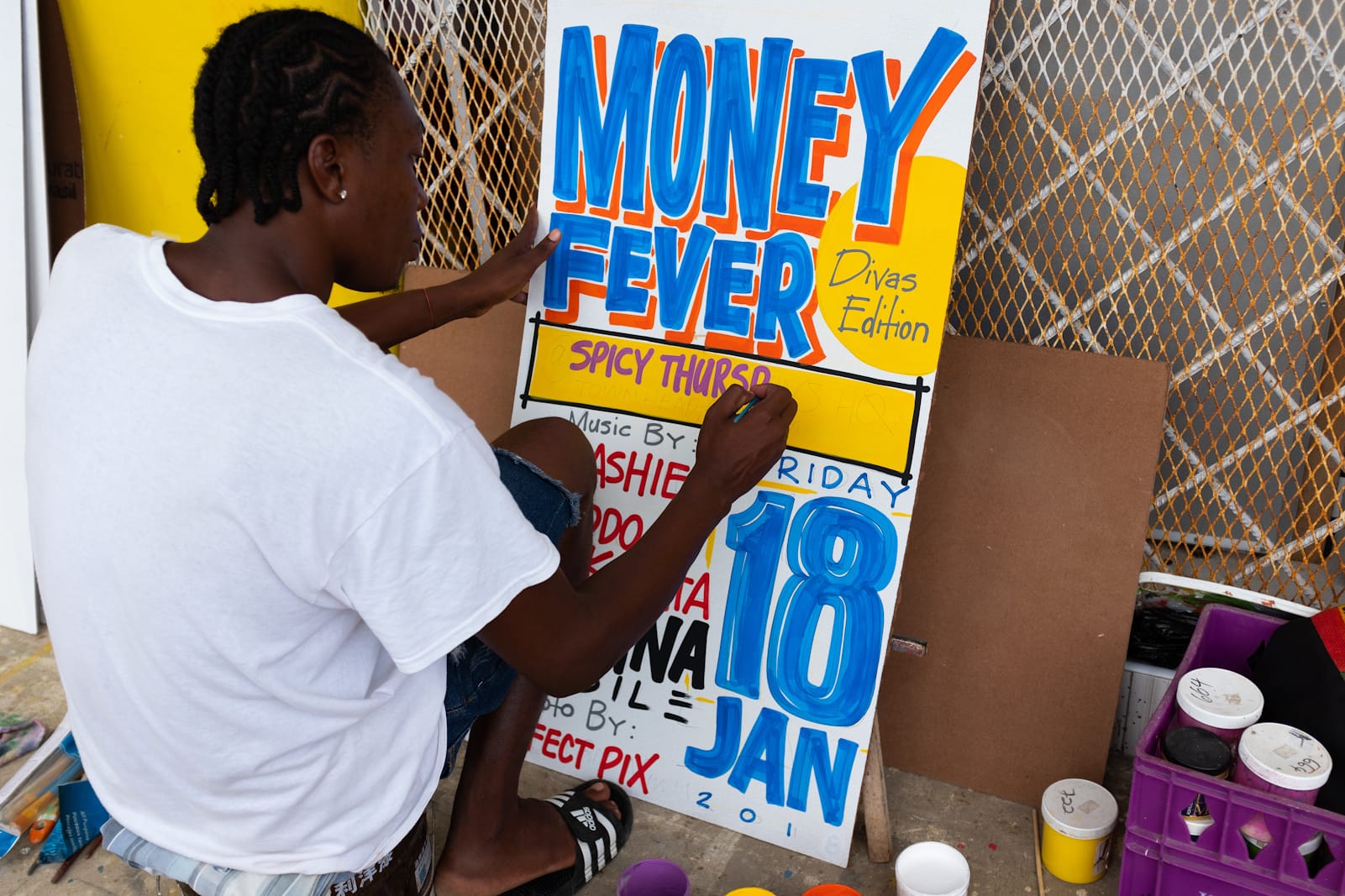

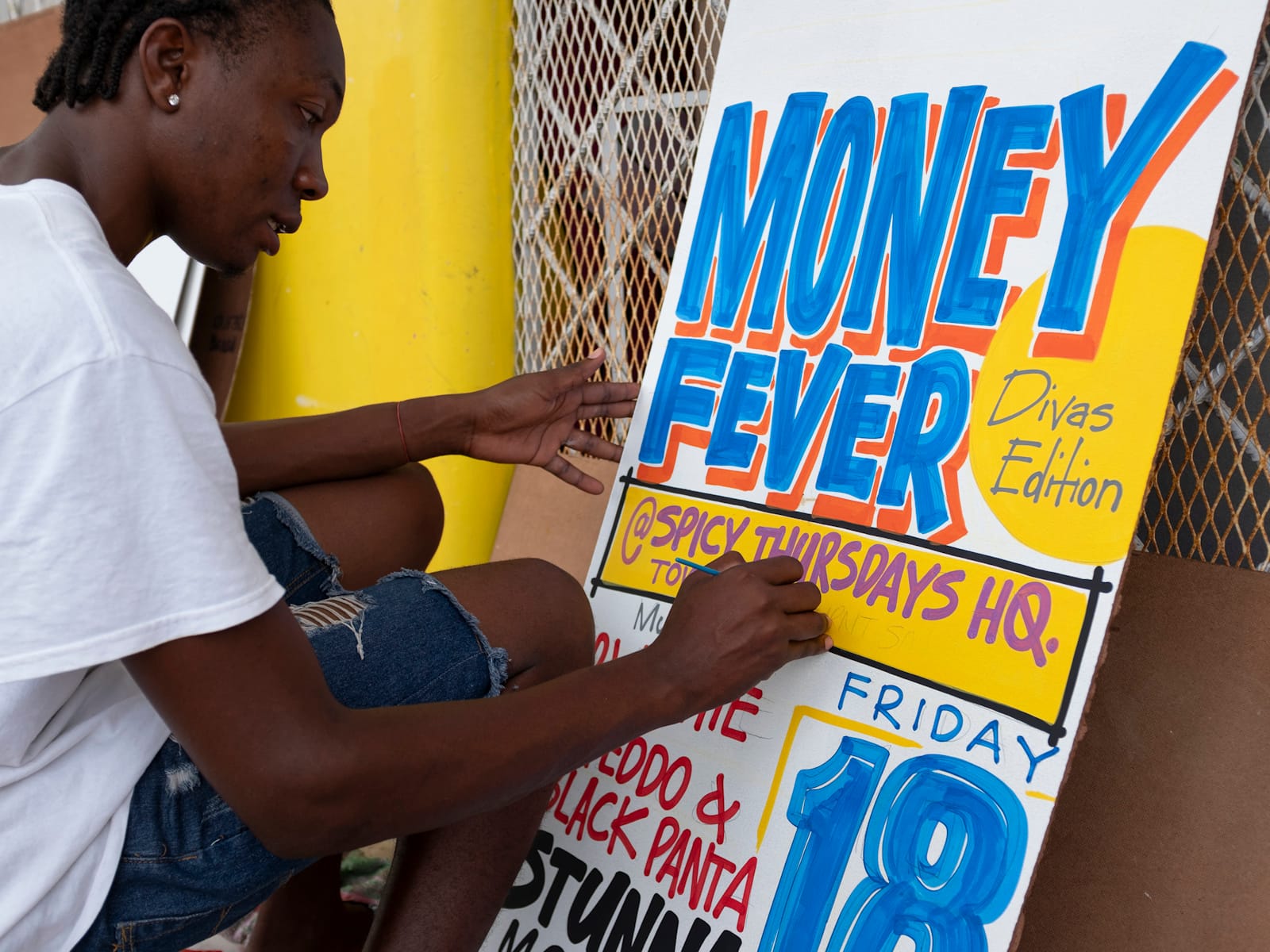

Work in progress and the finished ‘Money Fever’ Dancehall sign on ply, photographed in 2018 at Bug’s old sign studio in Savanna La Mar, Westmoreland, Jamaica.

Unlike Britain, where the rise of digital design and printed signage largely erased the craft by the late twentieth century, Jamaica has preserved it. Hand-painted signs remain an everyday sight, although my Hand-Painted Jamaica research revealed that the practice is slowly declining. Artists like Bug keep it alive, infusing it with a post-independence vibrancy.

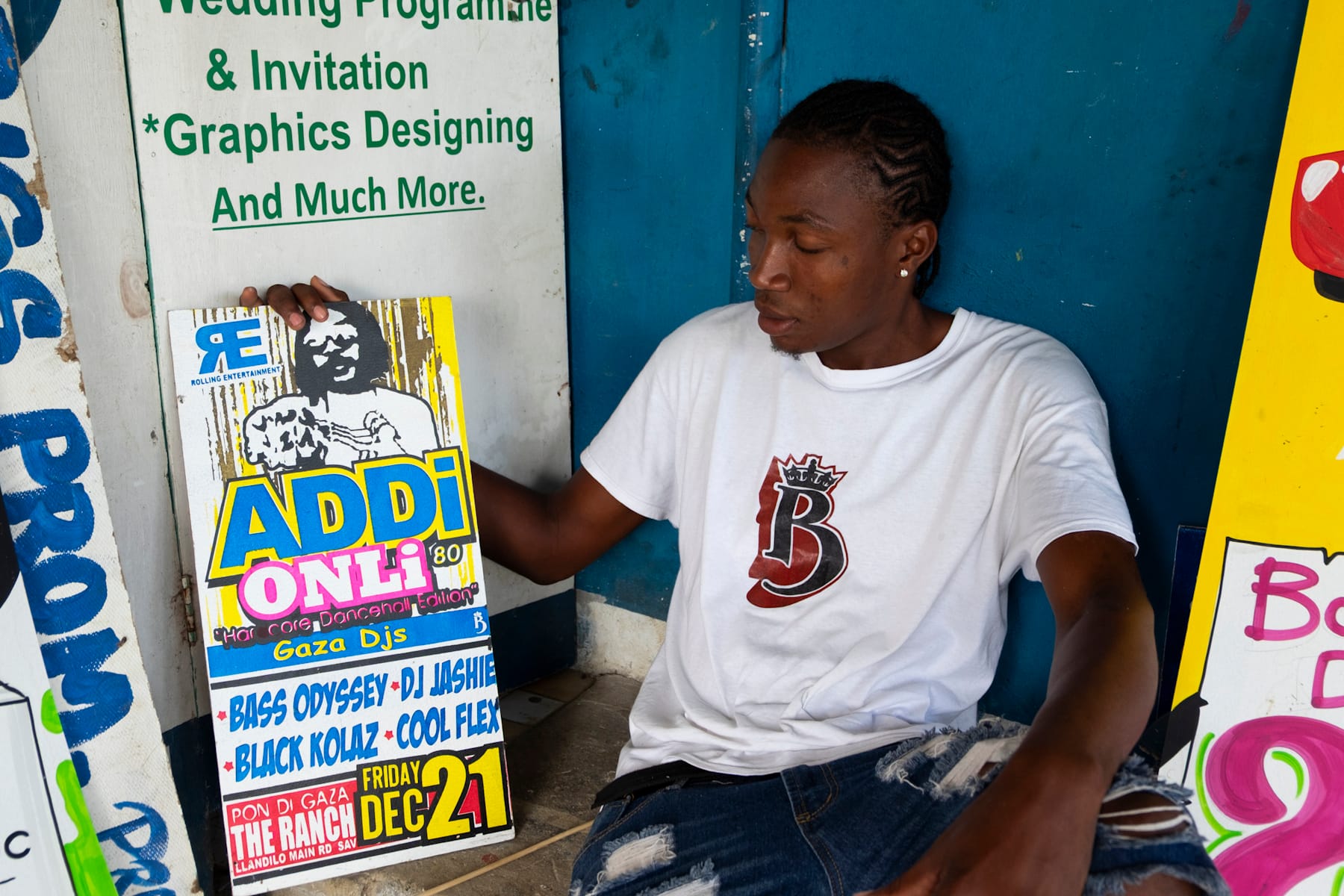

Over time, Bug has also adapted, blending tradition with efficiency. He continues to hand-paint commissions, but he’s learned to translate his designs into other formats using digital tools and screenprinting. When I visited him again in 2023, I found him at work printing a large batch of party signs; bold, colourful sheets that carried the same energy and hand-drawn character of his painted work. These signs were destined for the roadsides and crossroads of Westmoreland, where party promoters line the streets with announcements of upcoming events.

The screenprinting process allows Bug to keep his distinctive visual language in circulation, even at scale. It is a a meeting point between old and new methods that keeps Jamaica’s sign-painting tradition visible in everyday life.

When I interviewed Bug, he described his work as “Jamaica’s graffiti” — a nod to the visual language of hip-hop and the influence of street art from New York, but deeply rooted in Jamaica’s own cultural soundscape. If hip-hop graffiti mirrors the beat of the Bronx, then Jamaican sign painting dances to the rhythm of dancehall.

I’ve watched Bug paint — sometimes small boards, sometimes whole walls. His brush moves quickly and confidently, guided by muscle memory and music. Each piece is part performance, part preservation. His signs might advertise a party or a local business, but they also carry a lineage — one brushstroke at a time — of a tradition that links craftsmanship, independence, and visual storytelling.

Bug Art Sav’s work is a reminder that Jamaica’s visual identity isn’t found only in galleries or curated collections. It lives on the streets, on plywood, on zinc, and on hand-written walls, full of life, and still speaking.

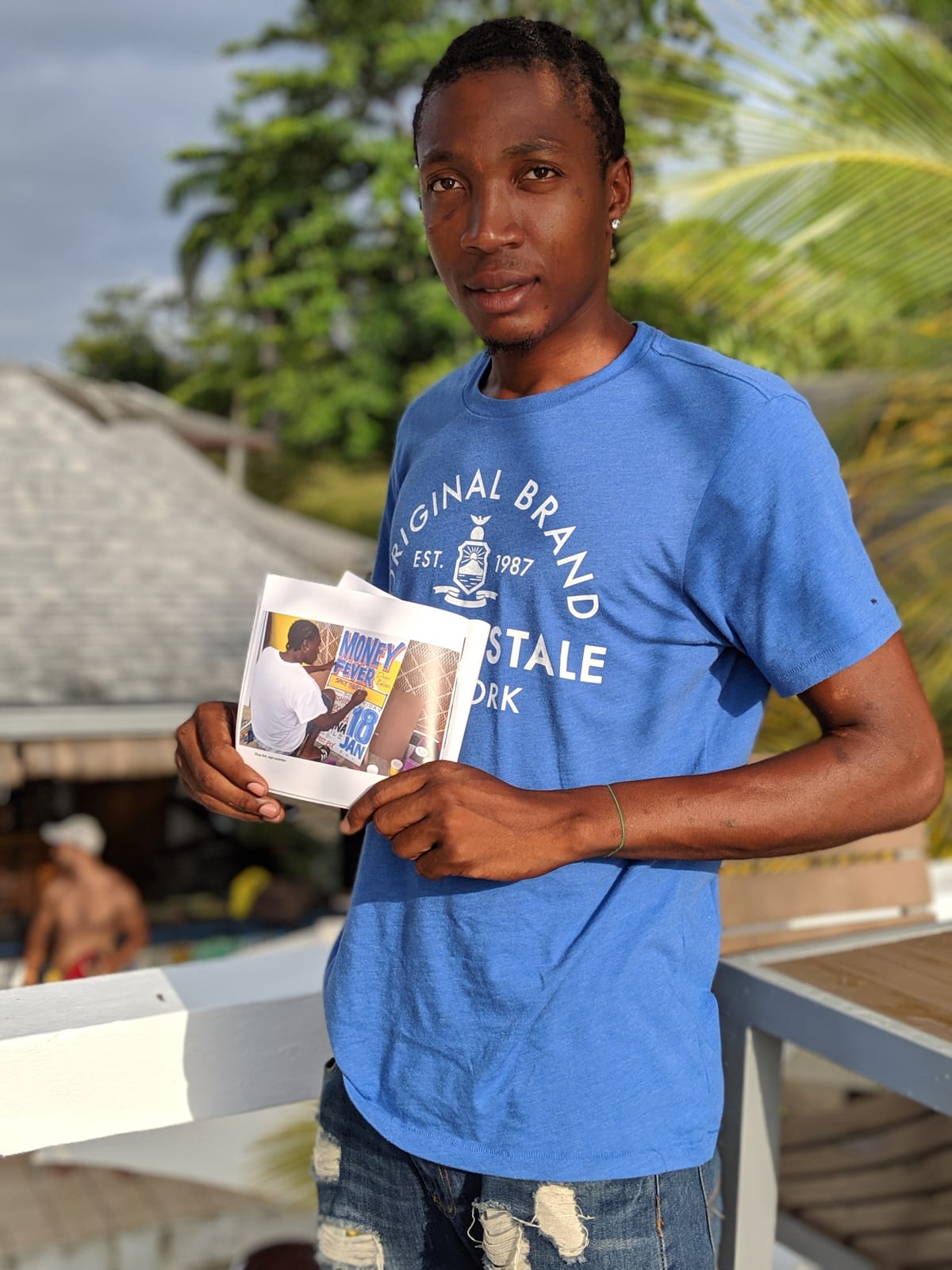

I featured some of Bug’s work in two zines and in an exhibition in Birmingham, UK, in 2019. After producing the exhibition and printing the Hand-Painted Jamaica zine, I returned to Jamaica in 2020 to give him copies. We’ve stayed in touch since then, and I continue to follow his work — watching how it evolves and how, as part of a younger generation of sign painters, he carries forward the legacy of keeping hand-painted sign art alive in Jamaica.

Tracey Thorne / Hand-Painted Jamaica

Bug Art Sav / @bug_art_sav

Notes

Friends of Bug Art have set up a GoFundMe page to help him rebuild after Hurricane Melissa.

Bug has a young family and lives just outside Savanna La Mar in Westmoreland, the area most impacted by the hurricane in eastern Jamaica. As you can imagine, the streets and local businesses, plus tourism, are central to his livelihood.

Recovery will be tough. Bug is a young sign painter who, after the last few years, has begun to connect with people around the world and link in with the global sign community. Some sign painters, after reading about him through my work and things published by BLAG / Better Letters, have been out to Negril and visited him. Hopefully, we can provide some love and support now. Whatever you can do, from following him on Instagram to donating to the GoFundMe, will be hugely appreciated.

More Hand-Painted Jamaica